Read time: 12 minutes

The Paris 2024 Olympic Games are over and I had a great time watching that epic closing ceremony with the family. If you have not watched it, you should at least check out the epic handoff of the Olympic flag by Tom Cruise.

If you got last week’s newsletter, where I covered Entra ID, here is one quick follow-up: It ended up being much easier to use the standard OIDC middleware than using the Microsoft Identity Web authentication libraries. So, I won’t be using (nor recommending) those libraries any time soon.

With that sorted out, I started this week with high hopes of getting the Game Store application deployed to Azure. However, a few key learnings around Kafka, Azure Event Hubs, and MassTransit took me down an unplanned side quest.

On to this week’s update.

Kafka and Azure Event Hubs are so different

In the upcoming .NET Bootcamp, I want to introduce students to the event streaming world using popular tech you can run locally, like Kafka, and leave the more complex Azure equivalent (Azure Event Hubs) for later modules fully dedicated to cloud deployment.

In theory, Kafka and Azure Event Hubs are very similar services. They both allow you to stream events into a very long event log that any of your applications can subscribe to at any time.

So when I was preparing my Game Store application for deployment, I started with the same plan I used for RabbitMQ and Azure Service Bus:

- Use MassTransit to switch between Kafka and Azure Event Hubs at startup time and keep the rest of the app agnostic of the underneath event streaming tech.

- Use .NET Aspire to configure Kafka for local dev and Azure Event Hubs when deploying the app to Azure.

That should just work, right?

Well, not quite, because of a few 2 important reasons:

1. MassTransit is not that good at event streaming

It works great with traditional message brokers, but to do event streaming you are supposed to use Riders, which makes consuming messages easy but does not help much with message production.

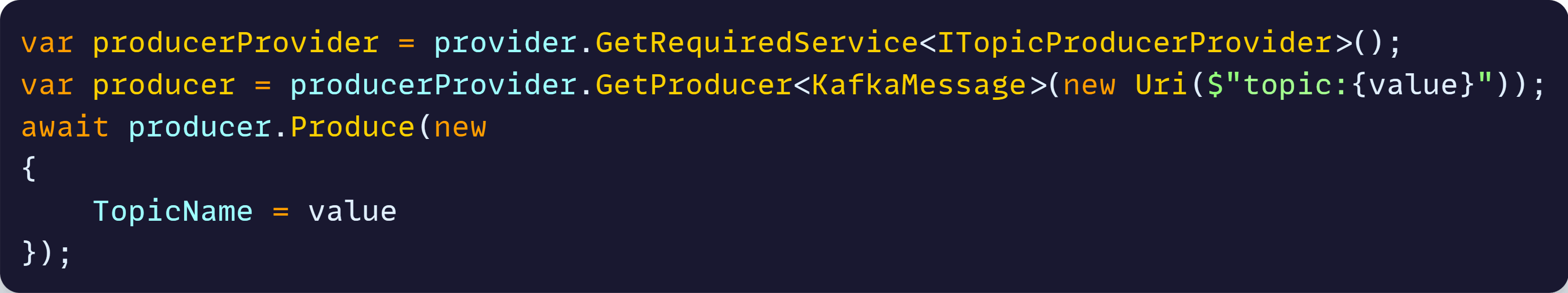

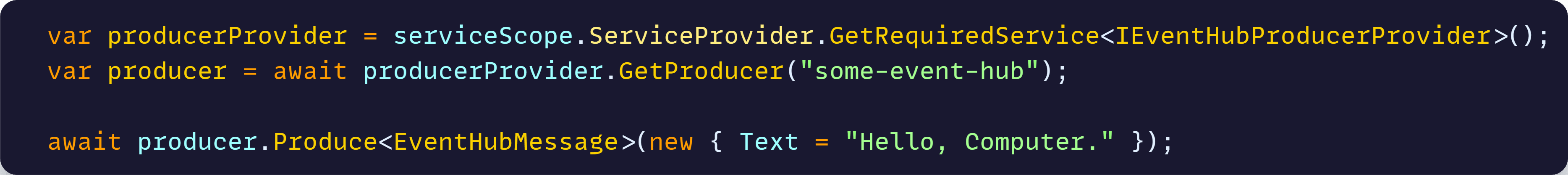

That’s because to produce messages for Kafka you use **ITopicProducer

But to produce messages to Azure Event Hubs you use IEventHubProducerProvider, like this

And, while the APIs are similar, they are fundamentally different, which means your application code will need to decide what to use depending on some sort of configuration, which is ugly.

On top of that, the way you configure those 2 with MassTransit on startup is just different, meaning you can’t just switch a connection string to point to Kafka or Event Hubs.

Plus, MassTransit pretty much forces you to have one Kafka topic per event type, which will significantly complicate things for microservices that want to know the current state of our product catalog, as I’ll explain later.

So, it’s a no-go.

2. Similar names, different things

In Kafka, you can easily auto-create topics and consumer groups on the fly, as needed by your apps, and with the right defaults.

On Azure Event Hubs, the equivalent to topics are hubs, and even when you can auto-create them on the fly, you have zero control over their default properties. This means we can’t enable Log Compaction (more on that later) by default, which is essential for the app.

Also, consumer groups are very different in each case. In Kafka, they are auto-created and they are key to storing the offsets. In Event Hubs, you have to create them manually, via the Azure Portal, CLI, Bicep or similar, and they don’t track offsets, but instead delegate that to an Azure Storage account.

Not good.

But, there is a way

Fortunately, I think the folks at Azure understood how important it is to enable Kafka-based apps to run on Azure, so they added a nice capability to Event Hubs.

You can use an Azure Event Hub as an endpoint for your Kafka applications, which enables you to connect to the event hub using the Kafka protocol. This without any code changes.

It is not as easy as just changing a connection string, but by applying 3 or 4 more settings to your Kafka configuration, your app will essentially think it is connecting to a Kafka cluster when it is actually using Azure Event Hubs.

The Azure Portal UI for Event Hubs is not as good as some Kafka UI’s, but I think it is an acceptable compromise given that you should be able to use any better UI to connect to Event Hubs via the Kafka protocol.

Now, let me explain a bit more about this important log compaction feature.

Why is log compaction important?

A core feature of our system is the ability to know the current state of resources tracked by a microservice not by making http calls to it, but by reading the event log.

So, for instance, if I stand up a new Promotions microservice that happens to need the full list of products owned by the Catalog microservice, we don’t make Promotions call Catalog’s HTTP API. We make Promotions read the event log that contains the changes to all products over time (produced by Catalog).

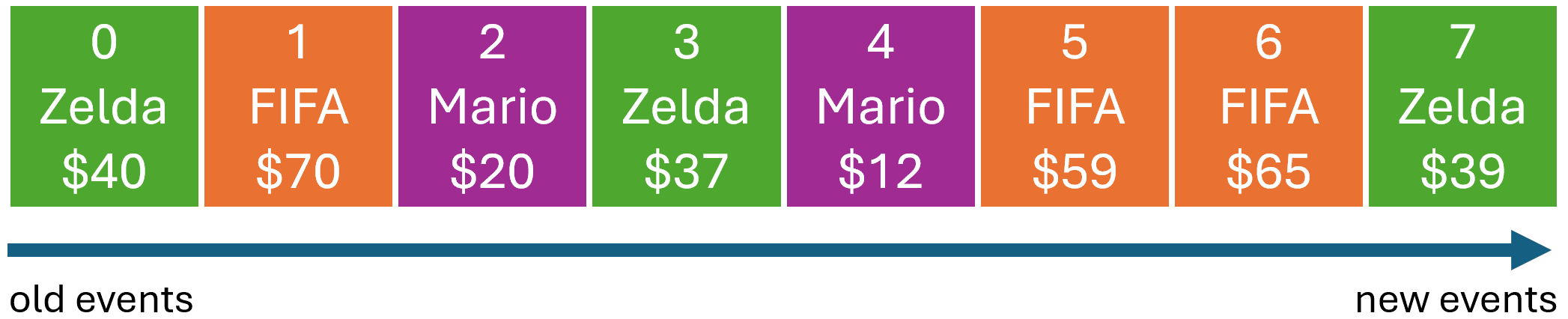

In this example, the numbers at the top are the log offsets, the game names are the log keys (you would use product ids normally, but names are easier to reason about) and the game prices at the bottom are the log values.

So, after going through a series of updates, currently the price of the Mario game is $12, FIFA goes for $65 and Zelda is at $39. But would this log not become really huge over time? How much time would it take for a microservice to read all that log to arrive at current products/prices?

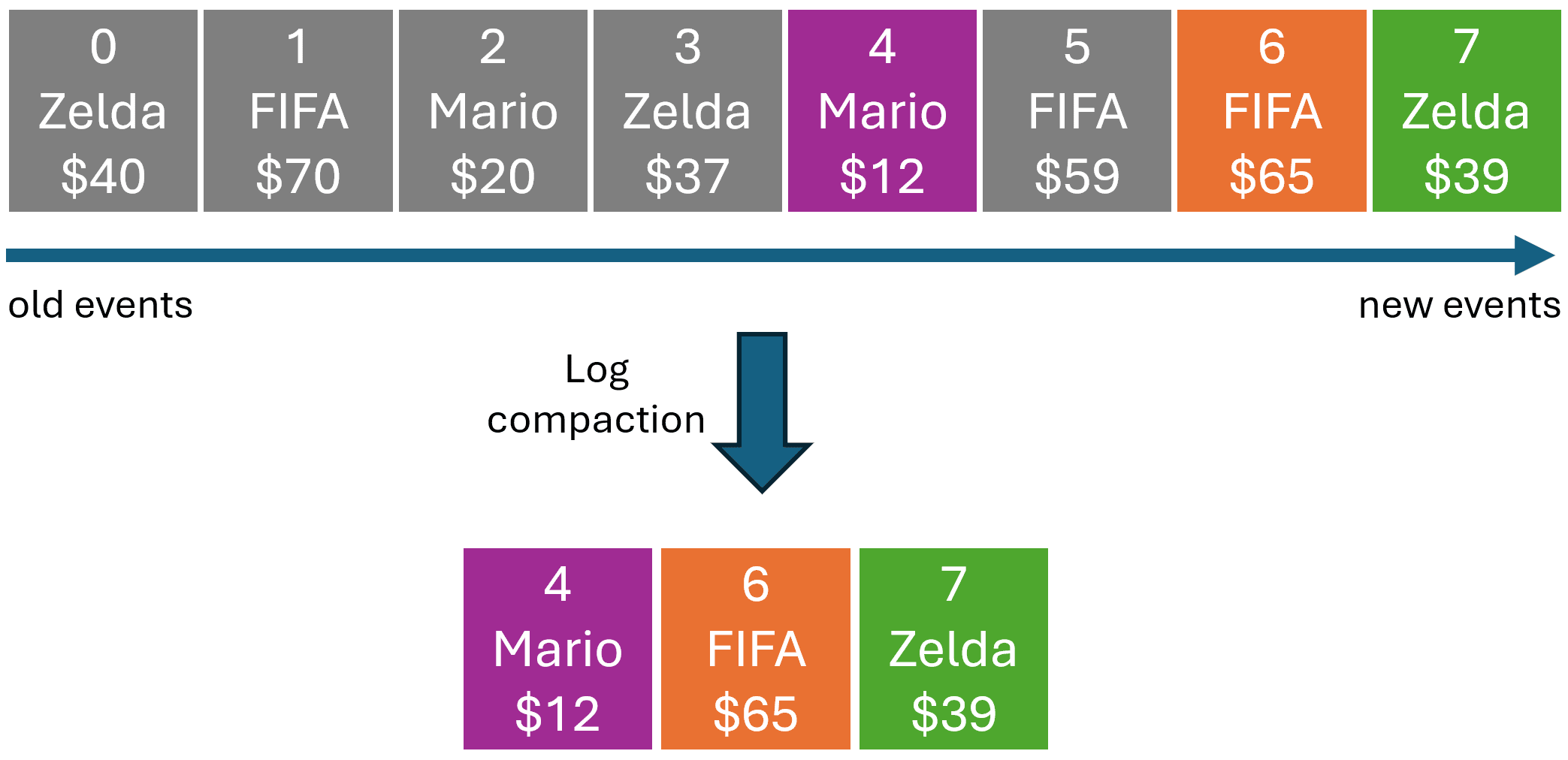

Here’s where we want to enable the Log Compaction feature, which instructs Kafka to keep only the most recent value for any given key. That way no microservice would need to read the entire log to know the current state of products.

Now this is a powerful and very useful feature, but it only works because the log contains an ordered list of all the events that affected all our products.

Which means we arrived at an important realization.

Order matters

So far I was following the common wisdom of having one topic per event type in the system. Meaning that, for the Catalog microservice, I had these 3 topics:

- catalog-game-created

- catalog-game-updated

- catalog-game-deleted

Which corresponded to the 3 events the microservice was producing.

But as I was polishing this, I had a feeling it would not work as intended. If events went to different topics, there is no guarantee that a consuming microservice would read events in the right order.

The Promotions microservice might totally read a “Mario game updated” event before reading the corresponding “Mario game created” event, resulting in it ending up with the initial price of the game, not the updated one.

So after a quick search, I landed on this great blog post by Martin Kleppmann, the guy behind the popular Designing Data-Intensive Applications book, which confirmed my theory.

So indeed, for all of this to work you can’t have topics per event type, even when it is common wisdom.

What to do then?

Many message types, single topic

The obvious solution is to have one topic per entity or, as that blog post also mentions:

“Any events that need to stay in a fixed order must go in the same topic”

Now, this is something that MassTransit does not naturally support, although you can make it work with some heavy hacking, which I’m not a fan of.

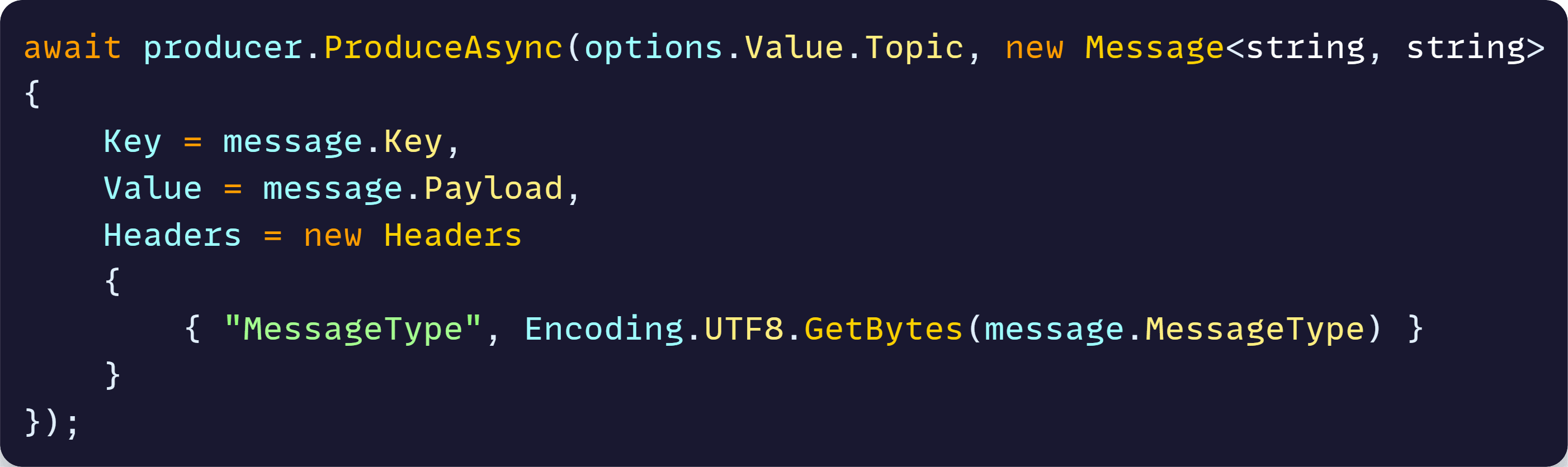

So I decided to implement my own producer and consumer logic using the native Kafka component provided by .NET Aspire.

Producing events via that component is fairly straightforward and looks like this when done by the OutboxProcessor used in the Catalog microservice:

The problem is on the other side: consuming those events on other microservices, like Basket and Ordering, which need an updated list of all products in the Catalog.

If all game updates go into a single Kafka topic now (catalog-games), how can consuming microservices differentiate and properly handle each event that lands there?

Well, the good thing is that Catalog exposes a Catalog.Contracts NuGet package that includes all events it publishes. So other microservices can use that to somehow deserialize the raw events into proper typed objects.

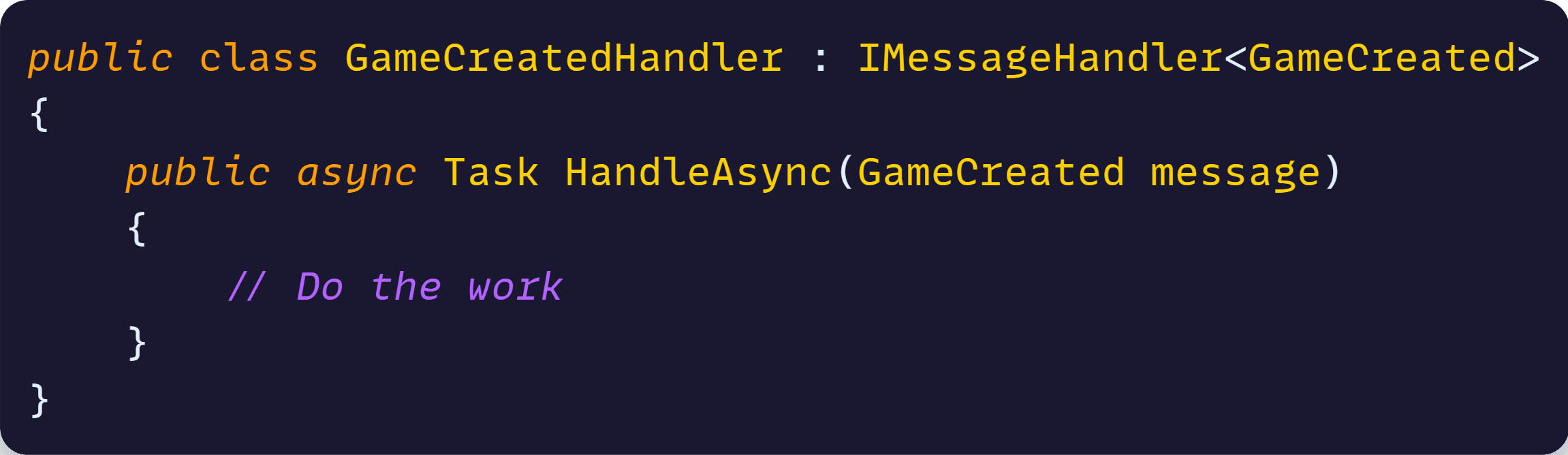

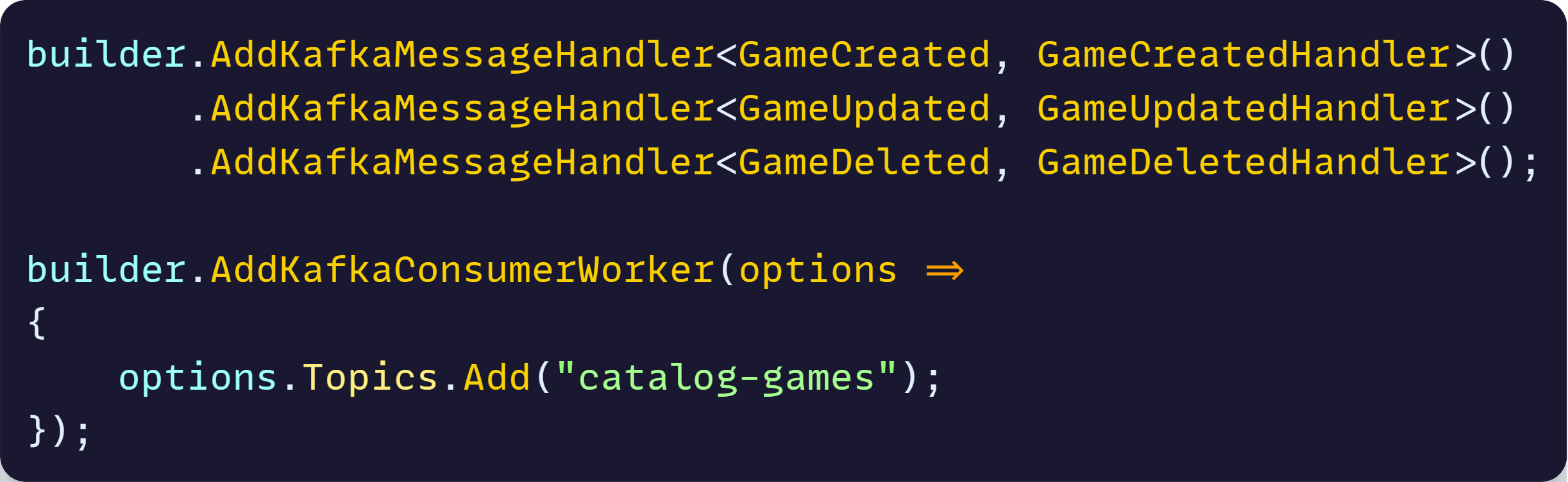

So what I wanted was to, ideally, land into a simple abstraction, similar to MassTransit consumers, that allowed me to do this:

Trying to get to that simple pattern took me a good while and made me really appreciate what MassTransit does for you in the case of traditional message brokers.

I thought about using MediatR here, but it would mean having my contracts get a dependency on that library, which is not great. Contracts should have zero dependencies on anything outside the standard types included with the .NET class libraries.

Took me a while, but found a better way.

Adapters and keyed services

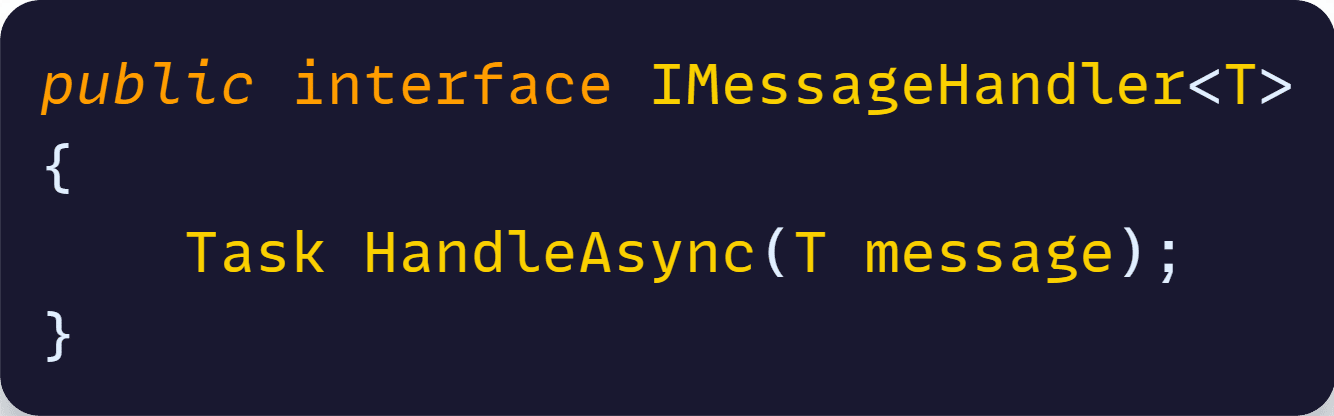

The solution started by introducing a simple interface that will handle messages for a given type, where T is the type of the event to handle:

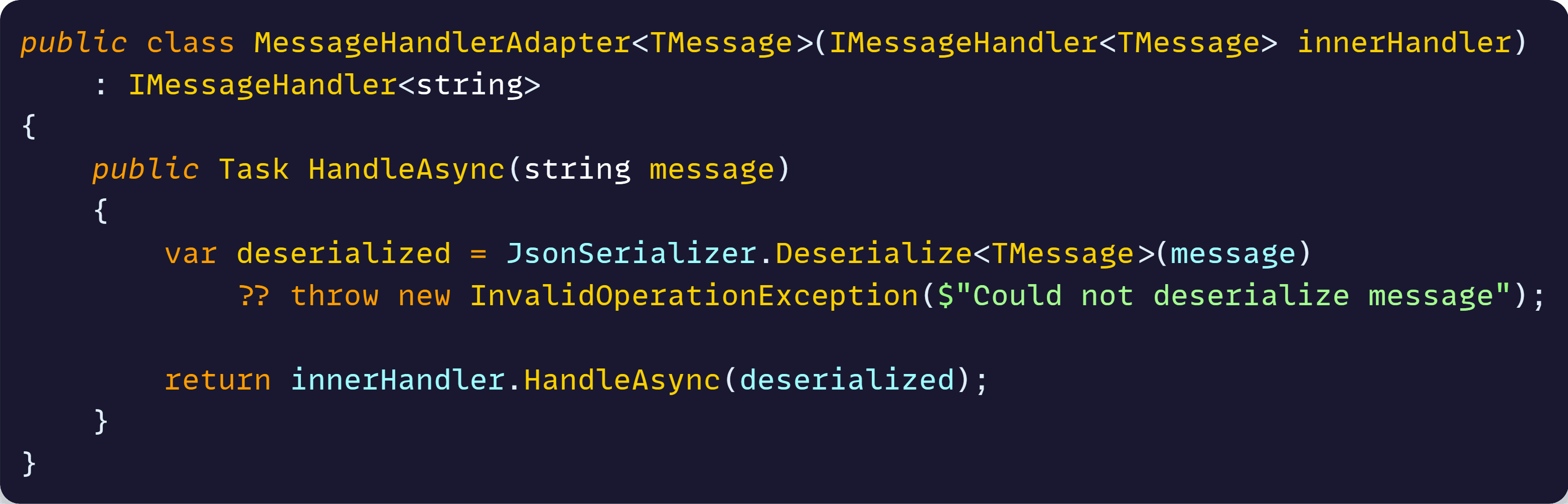

Then we create a small adapter class that implements this interface for the raw messages, which come as json strings, and deserializes the incoming message into the type expected by the inner message handler (the one the microservice will implement):

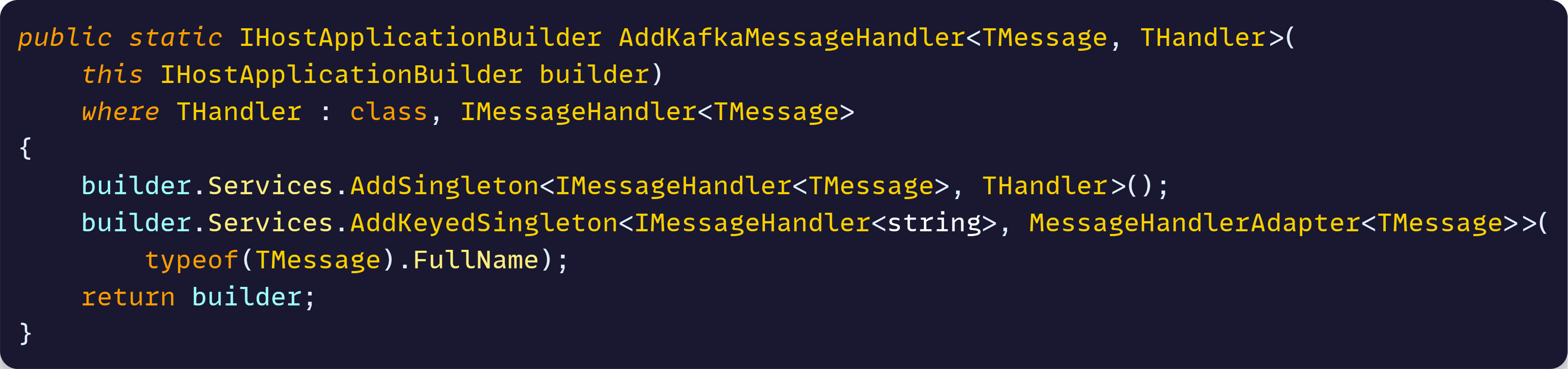

Then comes the really cool part: we implement an extension method that lets the microservice add a handler for a given message type by using the brand-new keyed services feature introduced in .net 8:

Notice that here we first register a simple singleton for the microservice handler, but we also register an additional keyed singleton for an adapter handler, where the key is the full name of the message type.

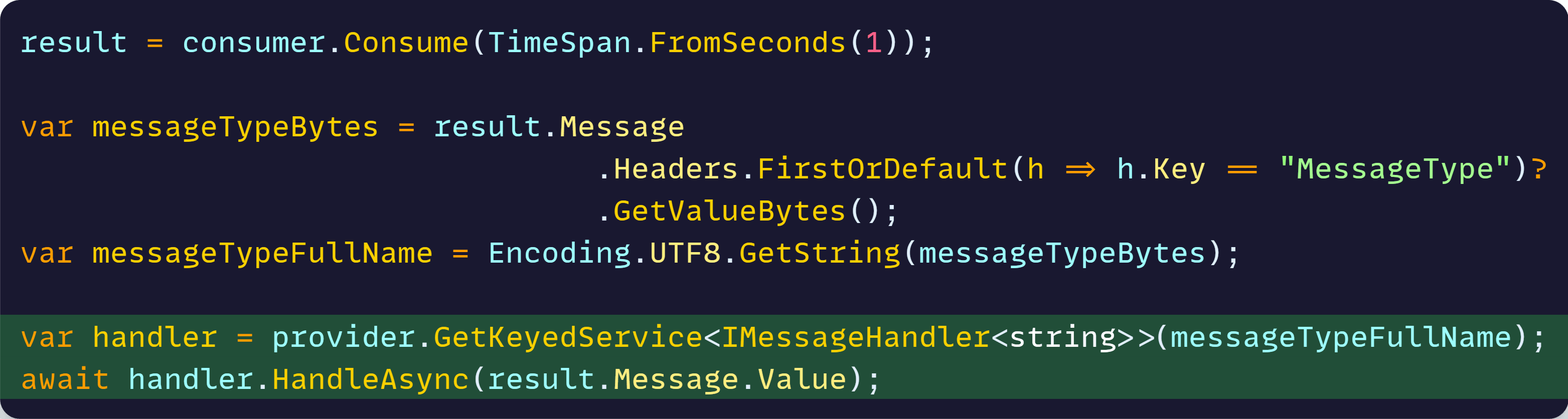

How does that help? Well, it helps because now we can do this fancy stuff in the background service that will consume events from the Kafka topic:

So the Kafka consumer background service consumes the message from Kafka, sends it over to the MessageHandlerAdapter and this one in turn deserializes it and sends it over to the microservice typed handler. Nice!

And, after adding one more extension method, our interested microservices can start consuming events by doing just this:

…and implementing handlers like the one I showed earlier.

Mission accomplished!

Closing

Arriving at this mini Kafka event consumer pattern was a wild ride, but as it usually happens, taking the time to understand the core concepts and apply the right patterns, can result in a really useful and flexible design that will save you tons of time and trouble in the future.

Until next time!

Julio

Whenever you’re ready, there are 3 ways I can help you:

-

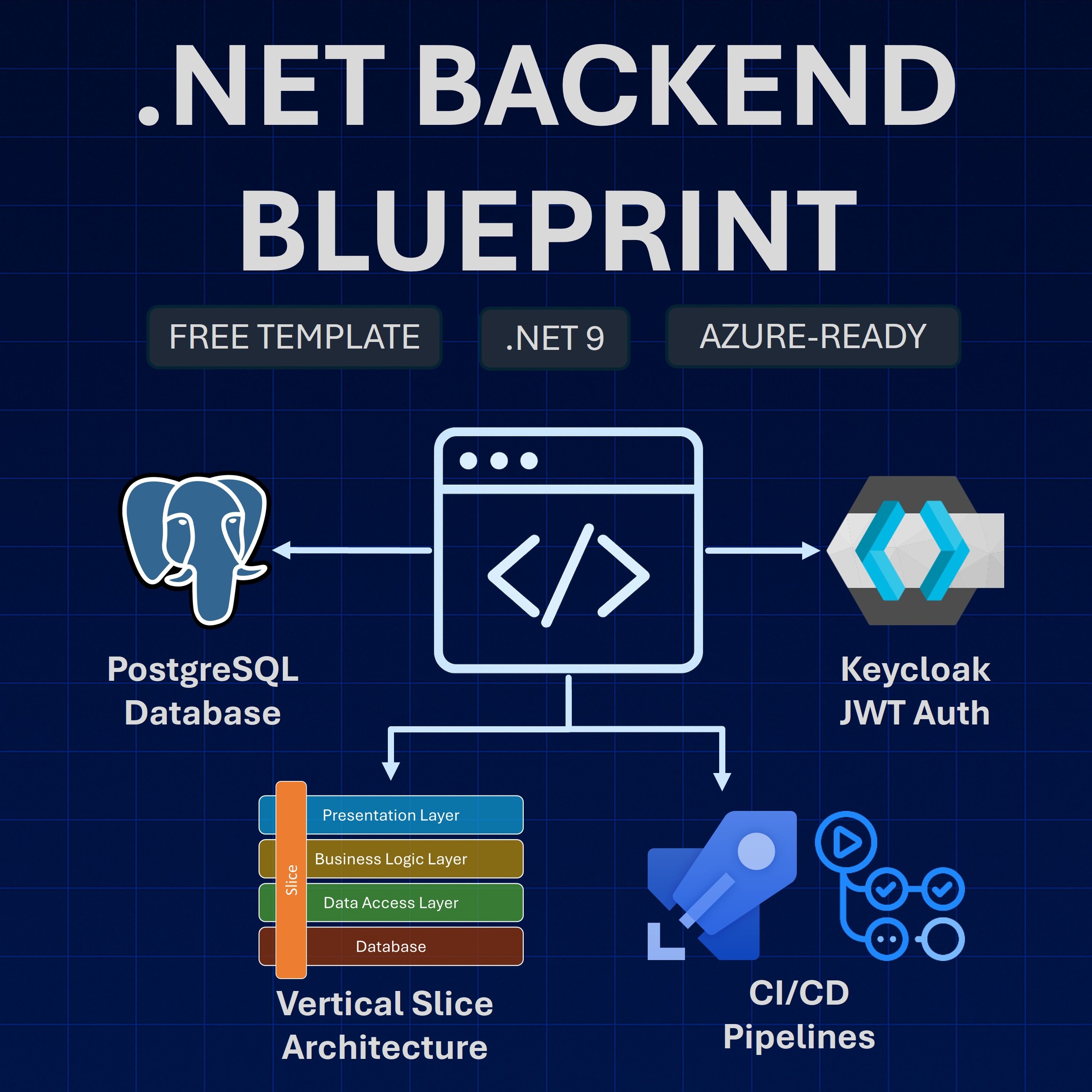

.NET Backend Developer Bootcamp: A complete path from ASP.NET Core fundamentals to building, containerizing, and deploying production-ready, cloud-native apps on Azure.

-

Building Microservices With .NET: Transform the way you build .NET systems at scale.

-

Get the full source code: Download the working project from this article, grab exclusive course discounts, and join a private .NET community.