Read time: 9 minutes

The .NET Saturday is brought to you by:

A few weeks ago, as I was preparing a suite of integration tests for the bootcamp’s Game Store app, I suddenly realized that writing a solid integration test for the queue processor is not a trivial task.

There’s plenty of documentation on how to write integration tests for .NET Web APIs, but for workers? Not so much.

Even worse, if your test needs to wait for a message to show up in a Service Bus queue so the worker processes it, you can end up with a very flaky and slow-moving test.

But it doesn’t have to be that way, since EF Core interceptors provide a really elegant way to get the job done without ever having to even touch your production code.

Today, I’ll show you the right way to do it.

Let’s start.

The scenario under test

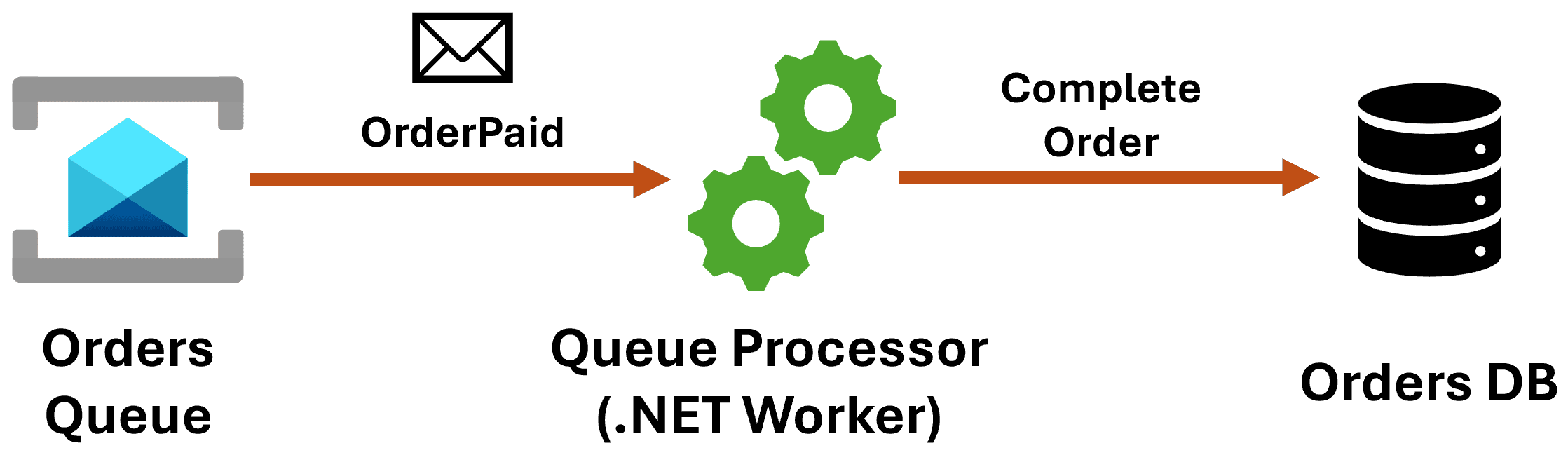

Our application includes a .NET worker responsible for reading OrderPaid messages from our Orders queue, fulfilling the order, and then updating its status to Completed in our database.

We could write all sorts of unit tests around the code used by our queue processor, but I find it more interesting to ensure that this .NET worker can update the Order status in a real database after consuming a real message from a real queue.

For that, an integration test is the best option. But first, let’s take a quick look at the worker logic.

The worker

There are two main elements to our .NET worker. The first one is our top-level logic to consume messages from the queue, a Service Bus queue in this case:

public class OrdersQueueProcessor(

ServiceBusClient serviceBusClient,

IServiceScopeFactory serviceScopeFactory) : BackgroundService

{

private ServiceBusProcessor? processor;

protected override async Task ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken stoppingToken)

{

processor = serviceBusClient.CreateProcessor(

"orders",

new ServiceBusProcessorOptions

{

AutoCompleteMessages = false

});

processor.ProcessMessageAsync += ProcessMessage;

processor.ProcessErrorAsync += ProcessError;

await processor.StartProcessingAsync(stoppingToken);

await Task.Delay(Timeout.Infinite, stoppingToken);

}

private async Task ProcessMessage(ProcessMessageEventArgs args)

{

var message = args.Message;

var messageBody = message.Body.ToString();

if (!message.ApplicationProperties.TryGetValue(

"MessageType",

out var messageTypeObj)

|| messageTypeObj is not string messageType)

{

await args.DeadLetterMessageAsync(message);

return;

}

await HandleMessageByType(messageBody, messageType, args.CancellationToken);

await args.CompleteMessageAsync(message);

}

private async Task HandleMessageByType(

string messageBody,

string messageType,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

switch (messageType)

{

case nameof(OrderPaid):

await HandleMessageAsync<OrderPaid>(messageBody, cancellationToken);

break;

default:

break;

}

}

private async Task HandleMessageAsync<T>(

string messageBody,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var message = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<T>(messageBody);

if (message is null)

{

return;

}

// Delegate handling to the appropriate message handler

using var scope = serviceScopeFactory.CreateScope();

var handler = scope.ServiceProvider.GetRequiredService<IMessageHandler<T>>();

await handler.HandleAsync(message, cancellationToken);

}

private Task ProcessError(ProcessErrorEventArgs args)

{

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}

I did have to remove a bunch of error checks and logging lines from that code, or it would be too long for this article, but this week’s source code download includes the complete version.

In essence, we start processing our orders queue in ExecuteAsync, and eventually, in HandleMessageAsync<T>, we deserialize the message and hand it over to a specialized handler.

That handler is over here:

public class OrderPaidHandler(

GameStoreContext context,

ILogger<OrderPaidHandler> logger

) : IMessageHandler<OrderPaid>

{

public async Task HandleAsync(

OrderPaid orderPaid,

CancellationToken ct = default)

{

var orderId = orderPaid.OrderId;

var order = await context.Orders

.Include(order => order.Items)

.FirstOrDefaultAsync(

order => order.Id == orderId, ct);

if (order is null)

{

logger.LogError("Order not found.");

return;

}

if (order.Status != OrderStatus.Processing)

{

logger.LogWarning(

"Order {OrderId} is not in Processing status",

order.Id);

return;

}

// Fullfill order (e.g., assign game codes, update inventory, etc.)

order.Status = OrderStatus.Completed;

await context.SaveChangesAsync(ct);

}

}

To keep it simple, all this handler does is update the Order status to Completed and persist that into the DB.

Now, what we need to test is this:

- OrdersQueueProcessor can consume real OrderPaid messages

- OrdersQueueProcessor delegates order processing to OrderPaidHandler

- OrderPaidHandler saves the updated order to our real DB

It’s not trivial, but there’s a way.

Making the worker testable

When you create worker services in .NET you usually get this code in your Program.cs file:

var builder = Host.CreateApplicationBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddHostedService<Worker>();

var host = builder.Build();

host.Run();

But unfortunately, that won’t work for our integration test since we need a way to not just start the worker as part of the test (so no host.Run()), but also to customize the Worker services to align with the testing environment.

That’s the kind of stuff that a WebApplicationFactory would do for you, if you were testing a Web App. But this is not a web app, it’s a background worker.

To make the worker testable, you can move the bulk of the startup code to another class capable of building and customizing the host, like this:

public static class WorkerHostBuilder

{

public static IHost Build(

string[]? args = null,

string? environmentName = null,

Action<IConfigurationBuilder>? configure = null,

Action<IServiceCollection>? testOverrides = null)

{

var settings = new HostApplicationBuilderSettings { Args = args };

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(environmentName))

{

settings.EnvironmentName = environmentName;

}

var builder = Host.CreateApplicationBuilder(settings);

configure?.Invoke(builder.Configuration); // Allow test overrides

builder.AddNpgsqlDbContext<GameStoreContext>("GameStoreDB");

builder.AddAzureServiceBusClient("serviceBus");

builder.Services.AddScoped<IMessageHandler<OrderPaid>, OrderPaidHandler>();

builder.Services.AddHostedService<OrdersQueueProcessor>();

testOverrides?.Invoke(builder.Services); // Allow test overrides

return builder.Build();

}

}

Notice how we not only register all our services here, but also open multiple doors for letting the caller specify a different environment, configuration settings, and even custom services to register.

And, with that in place, your Program.cs turns into just this:

using GameStore.Worker;

var host = WorkerHostBuilder.Build(args);

host.Run();

No difference in behavior, but let’s see how our test can now take advantage of our new WorkerHostBuilder.

The integration test

There are a bunch of moving pieces required to prepare our integration test. So let’s go over them step by step.

First, the test initialization:

public class OrdersWorkerTests : IAsyncLifetime

{

private readonly PostgreSqlContainer postgreContainer = new PostgreSqlBuilder().Build();

private ServiceBusContainer? serviceBusContainer;

private readonly Fixture fixture = new();

private static CancellationToken CancellationToken

=> TestContext.Current.CancellationToken;

public async ValueTask InitializeAsync()

{

await postgreContainer.StartAsync(CancellationToken);

fixture.Customize<DateTimeOffset>(o => o.FromFactory(() => DateTimeOffset.UtcNow));

var configFile = Path.Combine(

AppContext.BaseDirectory,

"Messaging",

"servicebus.config.json");

serviceBusContainer = new ServiceBusBuilder()

.WithAcceptLicenseAgreement(true)

.WithConfig(configFile)

.Build();

await serviceBusContainer.StartAsync(CancellationToken);

}

}

The key things to grasp from this code:

- We use Testcontainers to standup a real PostgreSQL server and Azure Service Bus emulator as Docker containers.

- We initialize AutoFixture, which we’ll use later to create our order.

- We provide a small config file to Service Bus, which describes the orders queue it needs to create for our test.

Now the first part of the test:

[Fact]

public async Task Consume_OrderPaid_CompletesOrder()

{

// 1) Ensure database exists and create an order in Processing state

var dbConnString = postgreContainer.GetConnectionString();

var sbConnString = serviceBusContainer!.GetConnectionString();

var dbOptions = new DbContextOptionsBuilder<GameStoreContext>()

.UseNpgsql(dbConnString)

.Options;

var orderId = Guid.NewGuid();

await using (var setupCtx = new GameStoreContext(dbOptions))

{

await setupCtx.Database.MigrateAsync(CancellationToken);

var order = fixture.Build<Order>()

.With(o => o.Id, orderId)

.With(o => o.Status, OrderStatus.Processing)

.With(o => o.Items, [.. fixture.Build<OrderItem>()

.With(i => i.Quantity, 2)

.CreateMany(1)])

.Create();

setupCtx.Orders.Add(order);

await setupCtx.SaveChangesAsync(CancellationToken);

}

// More code...

}

In this first part, we migrate our database using the connection string provided by our test container, and then we use AutoFixture to quickly prepare and persist an order in the correct state.

Next, the cool part:

// 2) Prepare an interceptor and start the worker host with DI overrides

var probe = new OrderCompletedInterceptor(orderId);

using var host = WorkerHostBuilder.Build(

environmentName: "Testing",

configure: configBuilder =>

{

var overrides = new Dictionary<string, string?>

{

["ConnectionStrings:GameStoreDB"] = dbConnString,

["ConnectionStrings:serviceBus"] = sbConnString

};

configBuilder.AddInMemoryCollection(overrides);

},

testOverrides: services =>

{

// Remove existing DbContext registrations

services.RemoveAll<DbContextOptions<GameStoreContext>>();

services.RemoveAll<GameStoreContext>();

services.RemoveAll<IDbContextFactory<GameStoreContext>>();

// Now, register DbContext with the interceptor so it can observe SaveChanges calls

services.AddDbContext<GameStoreContext>((sp, options) =>

{

options.UseNpgsql(dbConnString);

options.AddInterceptors(probe);

});

}

);

await host.StartAsync(CancellationToken);

That is where we take advantage of our new WorkerHostBuilder, by providing our own testing environment, configuration overrides, and our own logic to reconfigure the services injected into the worker.

But what is this OrderCompletedInterceptor object?

The interceptor

In the Entity Framework Core world, an interceptor is a class that can intercept, modify, and/or suppress EF Core operations.

It’s exactly what we need for our test, since we need to run some test-only logic exactly after our worker saves the order into the database:

public sealed class OrderCompletedInterceptor(Guid targetOrderId)

: SaveChangesInterceptor

{

private readonly TaskCompletionSource taskCompletionSource =

new(TaskCreationOptions.RunContinuationsAsynchronously);

public Task WaitAsync(TimeSpan timeout) =>

Task.WhenAny(taskCompletionSource.Task, Task.Delay(timeout))

.ContinueWith(t => taskCompletionSource.Task.IsCompleted

? Task.CompletedTask

: throw new TimeoutException(

"Order did not reach Completed in time."));

public override async ValueTask<int> SavedChangesAsync(

SaveChangesCompletedEventData eventData,

int result,

CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

if (!taskCompletionSource.Task.IsCompleted

&& eventData.Context is GameStoreContext ctx)

{

var order = await ctx.Orders.AsNoTracking()

.FirstOrDefaultAsync(

o => o.Id == targetOrderId, cancellationToken);

if (order?.Status == OrderStatus.Completed)

{

taskCompletionSource.TrySetResult();

}

}

return await base.SavedChangesAsync(

eventData,

result,

cancellationToken);

}

}

The key part of our interceptor is our SavedChangesAsync override, which will run just after our SaveChanges call in OrderPaidHandler.

What we do there is call TrySetResult on our TaskCompletionSource, so that the WaitAsync call can run to completion.

But who calls WaitAsync?

Completing the test

Going back to our integration test, we use a small publisher class I created to encapsulate the logic to publish the OrderPaid message to Service Bus:

// 3) Publish OrderPaid message

await using (var client = new ServiceBusClient(sbConnString))

{

var publisher = new ServiceBusMessagePublisher(

client,

NullLogger<ServiceBusMessagePublisher>.Instance);

await publisher.PublishAsync(

new OrderPaid(orderId),

queueName: "orders");

}

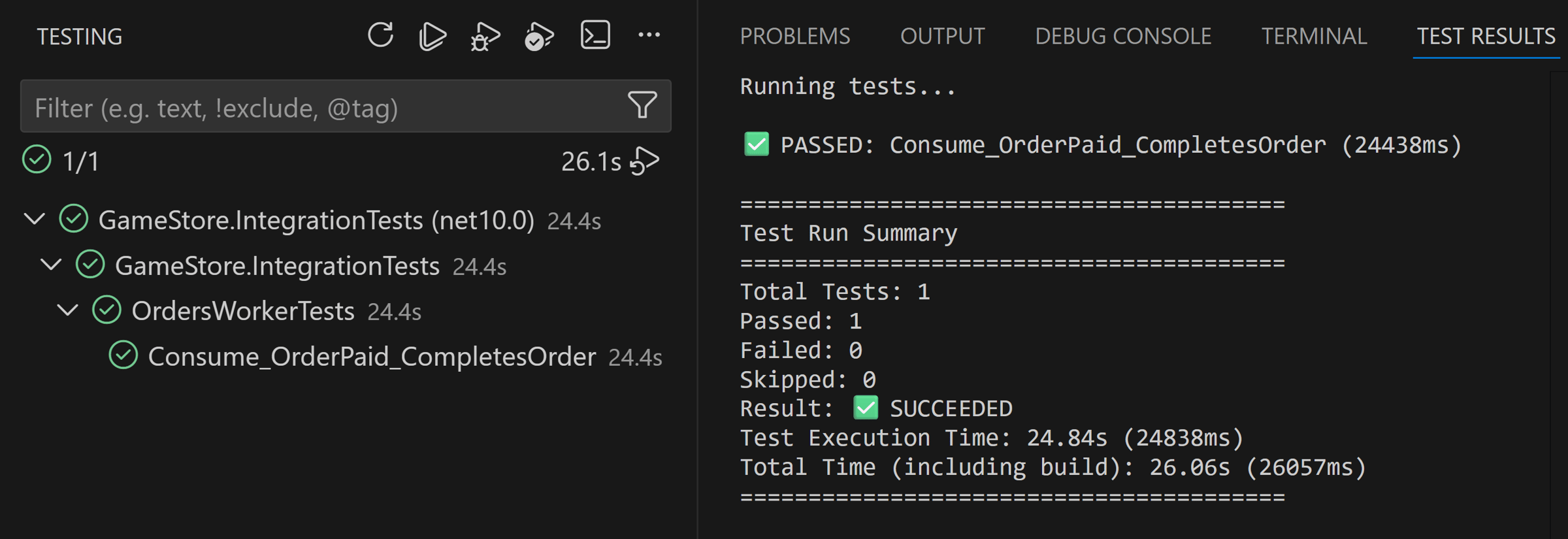

This puts things in motion, but it is at this point that we need to wait until that message is published, consumed by the worker, and the order is updated in the DB.

That’s when this next line comes in:

// 4) Wait for the worker to complete the order

await probe.WaitAsync(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30));

Yes, that’s where we call WaitAsync on the interceptor. We set a timeout just as a failsafe, but we should move past that line as soon as the interceptor catches the SaveChanges call.

After that, all we need is our assertions:

// 5) Assert – the order is in Completed state

await using (var assertCtx = new GameStoreContext(dbOptions))

{

var updated = await assertCtx.Orders

.AsNoTracking()

.Include(o => o.Items)

.FirstOrDefaultAsync(o => o.Id == orderId, CancellationToken);

updated.ShouldNotBeNull();

updated!.Status.ShouldBe(OrderStatus.Completed);

}

// Cleanup

await host.StopAsync(CancellationToken);

And with that, we have a reliable and (relatively) fast way to verify this complete flow, while exercising all of our real code with real dependencies:

Mission accomplished!

Wrapping up

Testing background workers often feels like gambling with race conditions. You usually find yourself adding Task.Delay calls to your tests and hoping the worker finishes in time.

By using EF Core interceptors, you eliminate the guesswork. You stop waiting for a timer and start waiting for the actual completion signal from your database.

Reliable tests rely on signals, not luck.

This is how you turn a flaky, slow-moving test suite into a deterministic one that you can actually trust to deploy to production.

And that’s it for today.

See you next Saturday.

Whenever you’re ready, there are 3 ways I can help you:

-

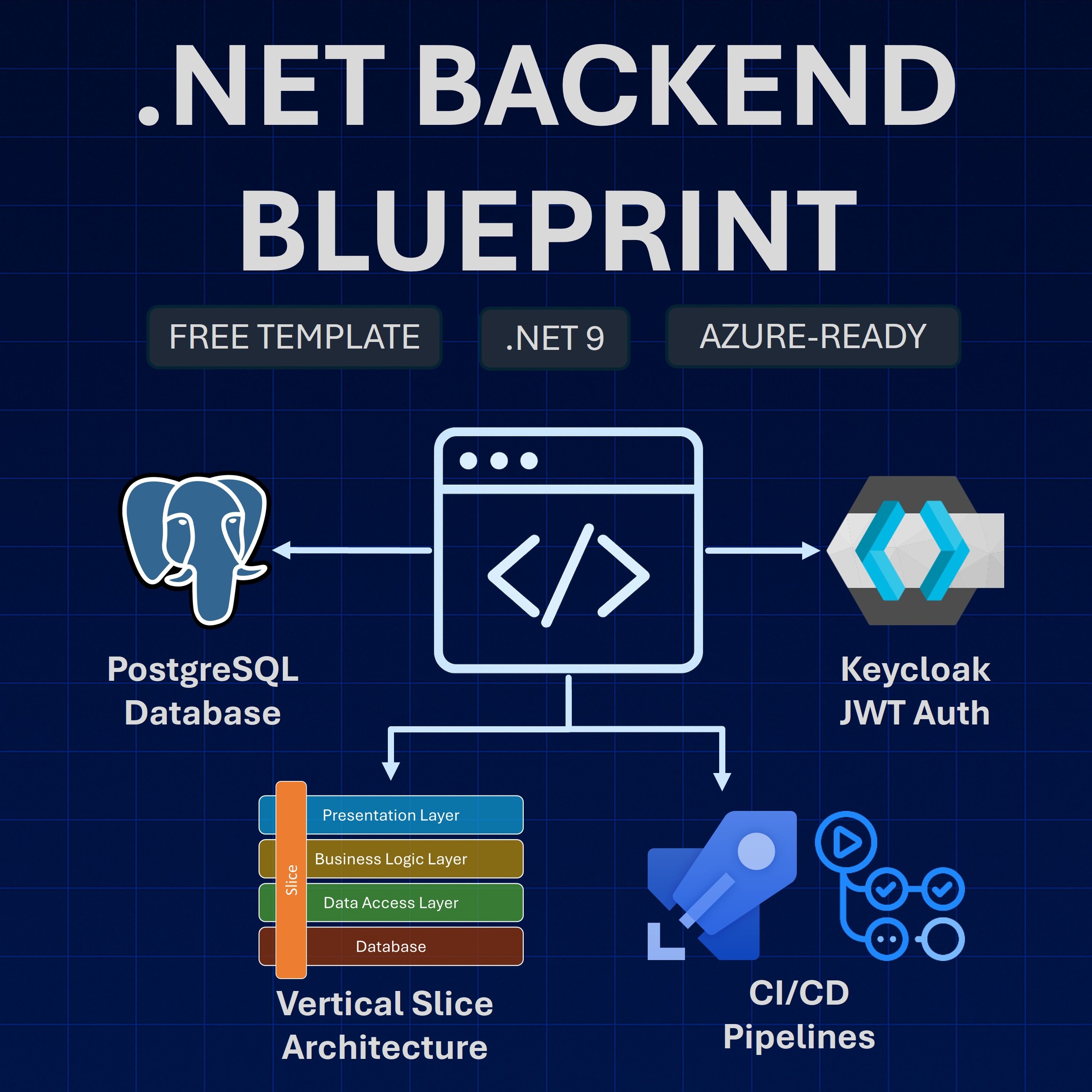

.NET Backend Developer Bootcamp: A complete path from ASP.NET Core fundamentals to building, containerizing, and deploying production-ready, cloud-native apps on Azure.

-

Building Microservices With .NET: Transform the way you build .NET systems at scale.

-

Get the full source code: Download the working project from this article, grab exclusive course discounts, and join a private .NET community.