Read time: 7 minutes

Last week, I was reviewing a pull request from a developer on my team. The code worked. Tests passed. But every business rule violation was handled by throwing an exception.

Invalid email? throw new ValidationException(). Username taken? throw new ConflictException(). User not found? throw new NotFoundException().

It works, but exceptions are meant for unexpected failures, not routine validation. There’s a better way.

Today, I’ll show you how the Result pattern gives you cleaner, faster, and more intentional error handling in ASP.NET Core.

Let’s start.

The Problem: Exceptions as Control Flow

Here’s a pattern I see all the time. A service that throws exceptions for every business rule violation:

public class UserService(AppDbContext db)

{

public async Task<User> CreateUser(string name, string email)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(name))

throw new ValidationException("Name is required");

if (!email.Contains('@'))

throw new ValidationException("Invalid email format");

if (await db.Users.AnyAsync(u => u.Email == email))

throw new ConflictException("Email already in use");

var user = new User { Name = name, Email = email };

db.Users.Add(user);

await db.SaveChangesAsync();

return user;

}

}

And then the endpoint has to catch all of them:

app.MapPost("/users", async (CreateUserRequest request, UserService service) =>

{

try

{

var user = await service.CreateUser(request.Name, request.Email);

return Results.Created($"/users/{user.Id}", user);

}

catch (ValidationException ex)

{

return Results.BadRequest(ex.Message);

}

catch (ConflictException ex)

{

return Results.Conflict(ex.Message);

}

});

Every new business rule means another custom exception class and another catch block. It gets messy fast.

Why This Is a Problem

Three reasons:

-

Performance: Throwing exceptions is expensive. The runtime has to unwind the stack, capture a stack trace, and allocate memory. For something that happens on every invalid form submission, that’s wasteful.

-

Intent: When you see a

throw, you expect something has gone seriously wrong. Using exceptions for “email already taken” dilutes their meaning. Is this a bug or a business rule? You can’t tell at a glance. -

Exceptions are for exceptional things: A user entering an invalid email is not exceptional. It happens all the time.

The Solution: A Simple Result Type

Instead of throwing, we return a Result<T> that explicitly says: “this either worked, or here’s what went wrong.”

public record Error(string Code, string Description, ErrorType Type);

public enum ErrorType

{

Validation,

Conflict,

NotFound

}

public class Result<T>

{

private Result(T value) { Value = value; IsSuccess = true; }

private Result(Error error) { Error = error; IsSuccess = false; }

public bool IsSuccess { get; }

public T? Value { get; }

public Error? Error { get; }

public static Result<T> Success(T value) => new(value);

public static Result<T> Failure(Error error) => new(error);

}

That’s it. No NuGet packages. No frameworks. Just a class that makes success and failure explicit in your return type.

Defining Your Errors

Instead of scattering error messages across your code, define them in one place:

public static class UserErrors

{

public static readonly Error NameRequired = new(

"User.NameRequired",

"Name is required",

ErrorType.Validation);

public static readonly Error InvalidEmail = new(

"User.InvalidEmail",

"Invalid email format",

ErrorType.Validation);

public static readonly Error EmailTaken = new(

"User.EmailTaken",

"Email is already in use",

ErrorType.Conflict);

}

Now every error has a code, a description, and a type. Clean, discoverable, and testable.

Refactoring the Service

Now our service returns a Result<User> instead of throwing:

public class UserService(AppDbContext db)

{

public async Task<Result<User>> CreateUser(string name, string email)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(name))

return Result<User>.Failure(UserErrors.NameRequired);

if (!email.Contains('@'))

return Result<User>.Failure(UserErrors.InvalidEmail);

if (await db.Users.AnyAsync(u => u.Email == email))

return Result<User>.Failure(UserErrors.EmailTaken);

var user = new User { Name = name, Email = email };

db.Users.Add(user);

await db.SaveChangesAsync();

return Result<User>.Success(user);

}

}

Notice how the method signature now tells you everything. It returns a Result<User>, meaning it might fail, and you have to handle that. No surprises.

Mapping Results to HTTP Responses

The last piece is translating a Result<T> into the right HTTP status code. A small extension method does the trick:

public static class ResultExtensions

{

public static IResult ToHttpResult<T>(

this Result<T> result,

Func<T, IResult> onSuccess)

{

if (result.IsSuccess)

return onSuccess(result.Value!);

return result.Error!.Type switch

{

ErrorType.Validation => Results.BadRequest(result.Error),

ErrorType.Conflict => Results.Conflict(result.Error),

ErrorType.NotFound => Results.NotFound(result.Error),

_ => Results.StatusCode(500)

};

}

}

And now your endpoint becomes beautifully simple:

app.MapPost("/users", async (CreateUserRequest request, UserService service) =>

{

var result = await service.CreateUser(request.Name, request.Email);

return result.ToHttpResult(user => Results.Created($"/users/{user.Id}", user));

});

No try/catch. No exception handlers. Just two clean lines that read exactly like what they do.

What About Existing Libraries?

If you don’t want to roll your own, there are solid options:

- FluentResults: lightweight, flexible, supports multiple errors and success messages

- ErrorOr: uses discriminated unions, plays nicely with minimal APIs

Both are great. But I’d still recommend understanding the pattern from scratch first (like we did above) before reaching for a library. It’s a simple pattern, and knowing how it works under the hood makes you a better consumer of any library.

The Takeaway

Exceptions should be for exceptional things: unexpected failures, infrastructure errors, things that shouldn’t happen during normal operation.

For everything else (validation, business rules, expected failures), the Result pattern gives you:

- Faster code (no stack unwinding)

- Clearer intent (the return type tells you it can fail)

- Easier testing (assert on result values, not catch blocks)

- Centralized error-to-HTTP mapping (one extension method, done)

And that’s it for today.

See you next Saturday.

Whenever you’re ready, there are 3 ways I can help you:

-

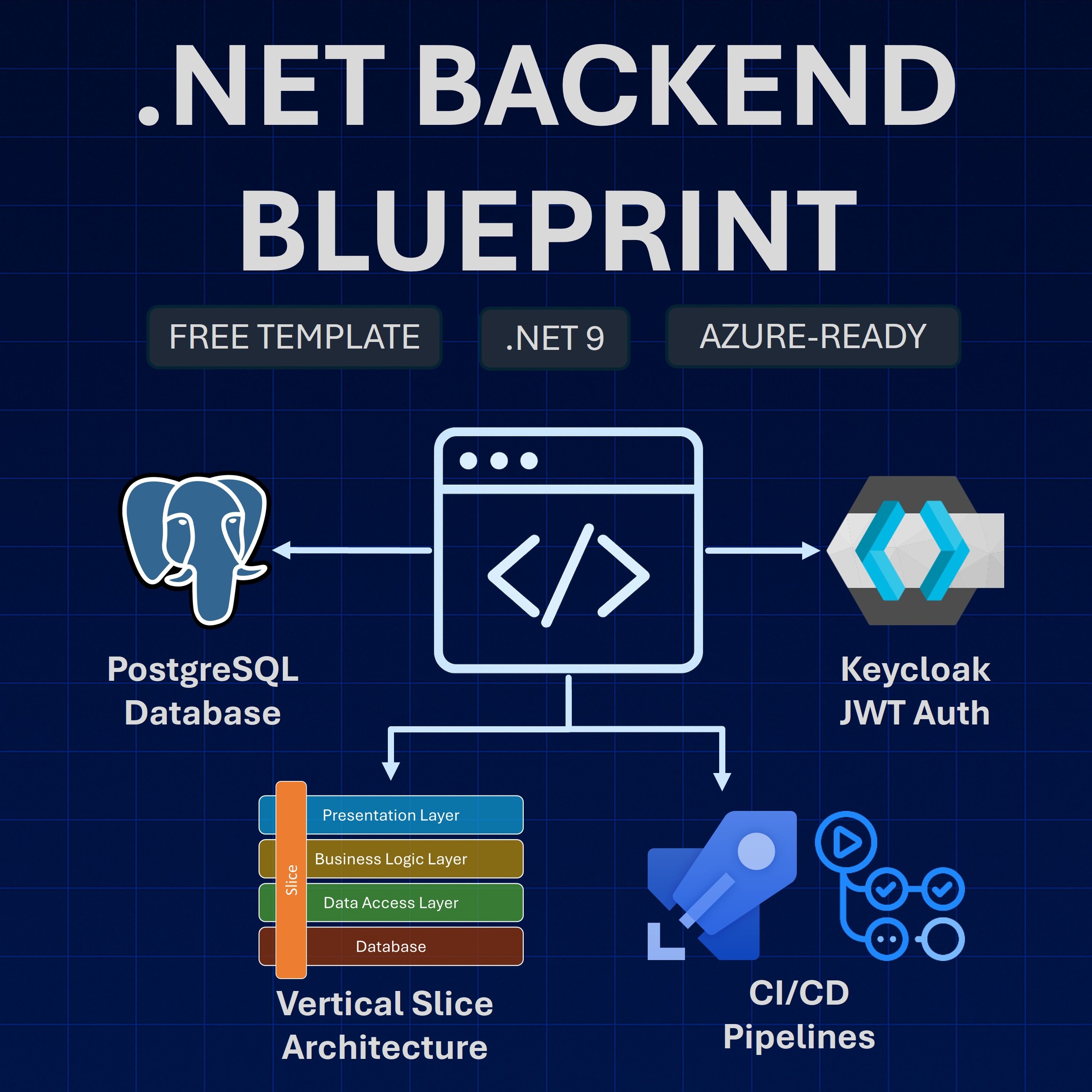

.NET Backend Developer Bootcamp: A complete path from ASP.NET Core fundamentals to building, containerizing, and deploying production-ready, cloud-native apps on Azure.

-

Building Microservices With .NET: Transform the way you build .NET systems at scale.

-

Get the full source code: Download the working project from this article, grab exclusive course discounts, and join a private .NET community.