Read time: 7 minutes

Writing clean code is essential for building maintainable, scalable, and bug-free software.

Clean code is easy to read, understand, and modify, making it easier to collaborate with other developers and maintain the codebase over time.

Unfortunately, most courses and schools won’t teach you how to write clean code, leaving you to figure it out on your own through trial and error.

So to save you some time and effort, here I’ll go over 5 key principles and best practices for writing clean code that you can start applying right away.

Let’s start.

1. Use Meaningful Names

Using meaningful names for variables, functions, and classes helps everyone on the team understand the codebase quickly and accurately.

For instance, take a look at this class from a role-playing game:

public class RPGCharacter

{

public int hp;

public int mp;

public int atk;

public int def;

public void atkRPG(RPGCharacter e)

{

e.hp -= this.atk - e.def;

}

public void h(RPGCharacter e)

{

e.hp += 10;

}

}

The class name RPGCharacter is meaningful, but the field and method names tell you nothing about what they mean or what they do.

Let’s refactor the class to use more meaningful names:

public class RPGCharacter

{

public int HealthPoints { get; set; }

public int ManaPoints { get; set; }

public int AttackPower { get; set; }

public int DefensePower { get; set; }

public void Attack(RPGCharacter enemy)

{

enemy.HealthPoints -= this.AttackPower - enemy.DefensePower;

}

public void Heal(RPGCharacter ally)

{

ally.HealthPoints += 10;

}

}

Now, the class is much easier to understand. The names of the fields and methods tell you exactly what they do.

So make sure you stick to meaningful names across all your classes to reduce the need for constant clarification, minimize errors, and make the code more maintainable.

2. Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

This principle states that a class should have only one reason to change. In other words, a class should have only one job or responsibility.

For example, imagine you’re building a simple note-taking app. You start by creating a Note class to represent each note.

Initially, you put everything related to a note in this class: the note’s text content, the date it was created, and even the logic for saving the note to a file.

public class Note

{

public string Content { get; set; }

public DateTime CreatedDate { get; set; }

public void SaveToFile(string filePath)

{

// ... (code to save the note's content to a file)

}

}

However, you soon realize this design has a few problems:

-

Tight Coupling: The Note class is directly tied to file saving, making it harder to change how notes are stored (e.g., using a database instead of files).

-

Testing: It’s difficult to test the note’s core functionality (content, creation date) without also having to deal with file saving.

-

Readability: The class is doing too much, making it harder to understand and maintain.

To solve these issues, you can refactor the class to follow the Single Responsibility Principle:

public class Note

{

public string Content { get; set; }

public DateTime CreatedDate { get; set; }

}

public class FileManager

{

public void SaveToFile(Note note, string filePath)

{

// ... (code to save the note's content to a file)

}

}

Now, the Note class only deals with note-related data, while the FileManager class handles file-saving logic.

This separation of concerns makes the code easier to maintain, test, and understand.

3. Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY)

DRY is a principle that encourages developers to avoid duplicating code. Instead, you should try to reuse existing code whenever possible.

For example, imagine you’re working on a web application and need to validate user input for various operations such as registration, login, and profile updates.

Here’s the initial version of your UserService class:

public class UserService

{

public string RegisterUser(string username, string password)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(username))

{

return "Username is required.";

}

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(password))

{

return "Password is required.";

}

// Registration logic...

return "User registered successfully.";

}

public string LoginUser(string username, string password)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(username))

{

return "Username is required.";

}

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(password))

{

return "Password is required.";

}

// Login logic...

return "User logged in successfully.";

}

public string UpdateProfile(string username, string password)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(username))

{

return "Username is required.";

}

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(password))

{

return "Password is required.";

}

// Profile update logic...

return "Profile updated successfully.";

}

}

Writing the same validation code for each operation can lead to errors and make maintenance difficult.

To follow the DRY principle, you can refactor the code to reuse the validation logic:

public class UserService

{

public string RegisterUser(string username, string password)

{

var validationResult = ValidateUser(username, password);

if (validationResult != "Valid")

{

return validationResult;

}

// Registration logic...

return "User registered successfully.";

}

public string LoginUser(string username, string password)

{

var validationResult = ValidateUser(username, password);

if (validationResult != "Valid")

{

return validationResult;

}

// Login logic...

return "User logged in successfully.";

}

public string UpdateProfile(string username, string password)

{

var validationResult = ValidateUser(username, password);

if (validationResult != "Valid")

{

return validationResult;

}

// Profile update logic...

return "Profile updated successfully.";

}

private string ValidateUser(string username, string password)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(username))

{

return "Username is required.";

}

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(password))

{

return "Password is required.";

}

return "Valid";

}

}

By creating a common ValidateUser method, you avoid repeating the same validation code in multiple places. This makes the code more maintainable and reduces the risk of errors.

4. Code Comments

Comments should be used sparingly and only to explain why something is done, not what is done.

For example, here is the initial version of the CalculateMonthlySalary method in our SalaryCalculator class:

public class SalaryCalculator

{

// Calculate the monthly salary for an employee

public decimal CalculateMonthlySalary(decimal annualSalary, int bonusPercentage)

{

// Check if annual salary is valid

if (annualSalary <= 0)

{

throw new ArgumentException("Annual salary must be greater than zero.");

}

// Check if bonus percentage is valid

if (bonusPercentage < 0)

{

throw new ArgumentException("Bonus percentage cannot be negative.");

}

// Calculate the monthly salary

decimal monthlySalary = annualSalary / 12;

// Calculate the bonus

decimal bonus = (annualSalary * bonusPercentage) / 100;

// Add bonus to monthly salary

monthlySalary += bonus / 12;

return monthlySalary;

}

}

CalculateMonthlySalary handles everything: validating inputs, calculating the monthly base salary, calculating the bonus, and combining them. Comments are used to explain each step, which makes the method longer and harder to read.

To improve the code, you can refactor it to separate concerns and remove unnecessary comments:

public class SalaryCalculator

{

public decimal CalculateMonthlySalary(decimal annualSalary, int bonusPercentage)

{

ValidateSalaryInputs(annualSalary, bonusPercentage);

decimal monthlyBaseSalary = CalculateMonthlyBaseSalary(annualSalary);

decimal monthlyBonus = CalculateMonthlyBonus(annualSalary, bonusPercentage);

return monthlyBaseSalary + monthlyBonus;

}

private void ValidateSalaryInputs(decimal annualSalary, int bonusPercentage)

{

if (annualSalary <= 0)

{

throw new ArgumentException("Annual salary must be greater than zero.");

}

if (bonusPercentage < 0)

{

throw new ArgumentException("Bonus percentage cannot be negative.");

}

}

private decimal CalculateMonthlyBaseSalary(decimal annualSalary)

{

return annualSalary / 12;

}

private decimal CalculateMonthlyBonus(decimal annualSalary, int bonusPercentage)

{

// The bonus is calculated annually and then divided by 12 to get the monthly portion

decimal annualBonus = (annualSalary * bonusPercentage) / 100;

return annualBonus / 12;

}

}

By breaking down the logic into smaller, focused methods, you eliminate the need for most comments. Each method now has a single responsibility, making the code easier to read and maintain.

The calculation of the monthly bonus still includes a comment to explain why the annual bonus is divided by 12, as this might not be immediately obvious.

So, use comments effectively to clarify non-obvious logic while keeping the rest of your code self-documenting.

5. Keep It Simple, Stupid (KISS)

The KISS principle states that simplicity should be a key goal in design, and unnecessary complexity should be avoided. Simple code is easier to understand, test, and maintain.

For example, imagine you’re building a small ASP.NET Core API to fetch and display user data from a database. Your project uses Entity Framework Core to interact with the database.

In your initial version, you decide to abstract the DB context into a separate repository class, which implements an IUserRepository interface, just in case you need to switch to a different database in the future.

So you end up with something like this:

// Define the User entity

public class User

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

}

// Define the database context

public class AppDbContext : DbContext

{

public DbSet<User> Users { get; set; }

public AppDbContext(DbContextOptions<AppDbContext> options) : base(options) { }

}

// Repository interface

public interface IUserRepository

{

User GetUserById(int id);

}

// Repository implementation

public class UserRepository : IUserRepository

{

private readonly AppDbContext context;

public UserRepository(AppDbContext context)

{

this.context = context;

}

public User GetUserById(int id)

{

return context.Users.FirstOrDefault(u => u.Id == id);

}

}

// Startup logic

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddDbContext<AppDbContext>(options =>

options.UseSqlServer("your connection string"));

builder.Services.AddScoped<IUserRepository, UserRepository>();

var app = builder.Build();

app.MapGet("/users/{id}", (int id, IUserRepository userRepository) =>

{

var user = userRepository.GetUserById(id);

if (user == null)

{

return Results.NotFound();

}

return Results.Ok(user);

});

app.Run();

That works, but it’s a bit over-engineered for a simple API. You’re unlikely to switch databases anytime soon, and the repository pattern adds unnecessary complexity.

To simplify the code and follow the KISS principle, you can remove the repository pattern and directly use the DbContext in your API:

// Define the User entity

public class User

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

}

// Define the database context

public class AppDbContext : DbContext

{

public DbSet<User> Users { get; set; }

public AppDbContext(DbContextOptions<AppDbContext> options) : base(options) { }

}

// Startup logic

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

builder.Services.AddDbContext<AppDbContext>(options =>

options.UseSqlServer("your connection string"));

var app = builder.Build();

app.MapGet("/users/{id}", (int id, AppDbContext context) =>

{

var user = context.Users.FirstOrDefault(u => u.Id == id);

if (user == null)

{

return Results.NotFound();

}

return Results.Ok(user);

});

app.Run();

There may be other valid reasons not to use the DbContext directly in your API, like in the case where the querying logic is too complex or needs to be reused in multiple places. By all means, refactor that code into a separate class in that case.

But don’t add unnecessary complexity to your codebase just because you think you might need it in the future. Keep it simple and only add complexity when you need it.

Key Takeaways

So, to write clean code, remember these key principles:

-

Use Meaningful Names: Make your code self-explanatory by using descriptive names.

-

SRP: Each class should have only one reason to change.

-

DRY: Avoid duplicating code by reusing existing logic.

-

Code Comments: Use comments sparingly to explain why something is done, not what is done.

-

KISS: Aim for simplicity in your code design and avoid unnecessary complexity.

By following these principles, you can write clean, maintainable code that is easy to understand and work with.

And remember, writing clean code is a skill that improves with practice. So keep coding, keep learning, and keep refining your code to make it cleaner and better.

Whenever you’re ready, there are 3 ways I can help you:

-

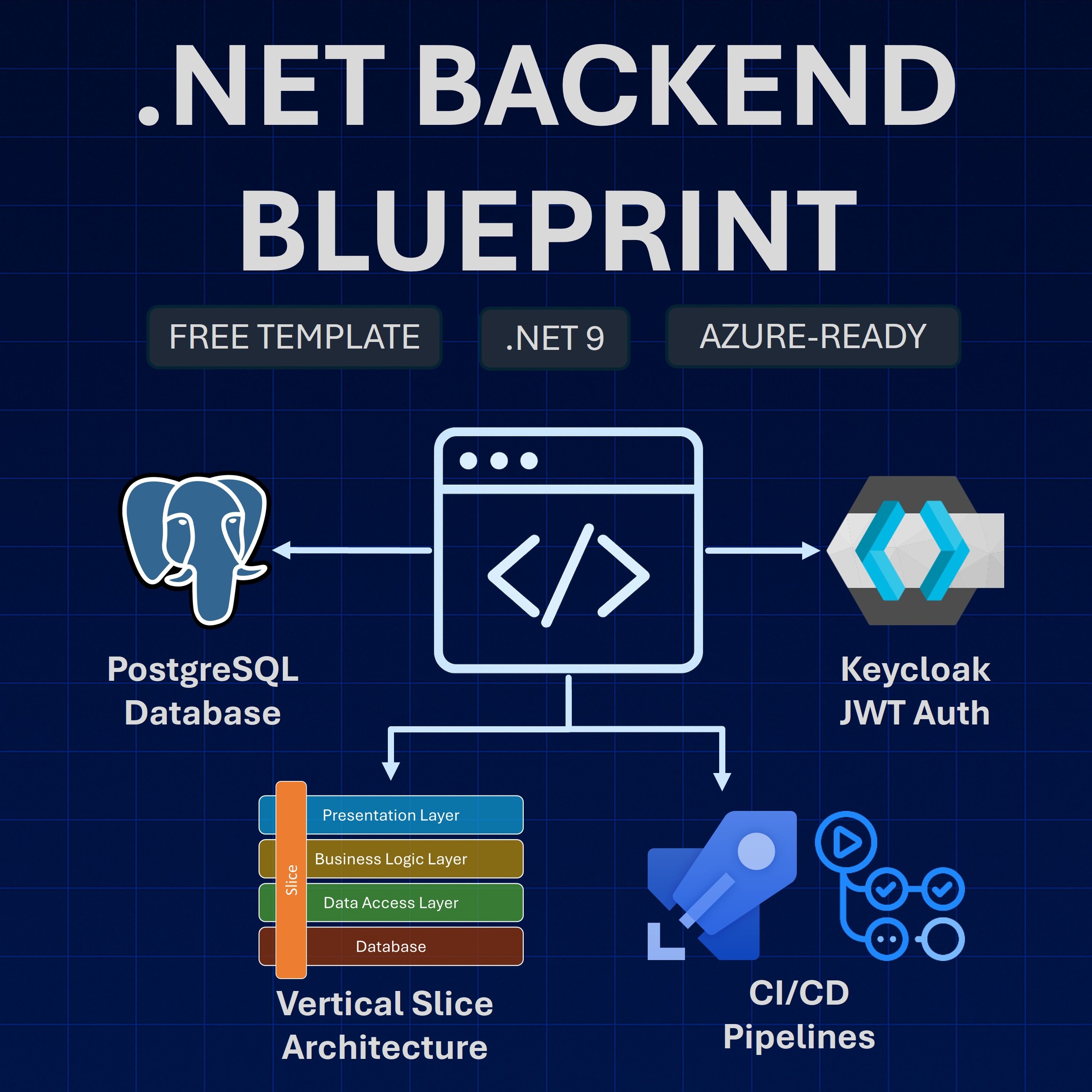

.NET Backend Developer Bootcamp: A complete path from ASP.NET Core fundamentals to building, containerizing, and deploying production-ready, cloud-native apps on Azure.

-

Building Microservices With .NET: Transform the way you build .NET systems at scale.

-

Get the full source code: Download the working project from this article, grab exclusive course discounts, and join a private .NET community.